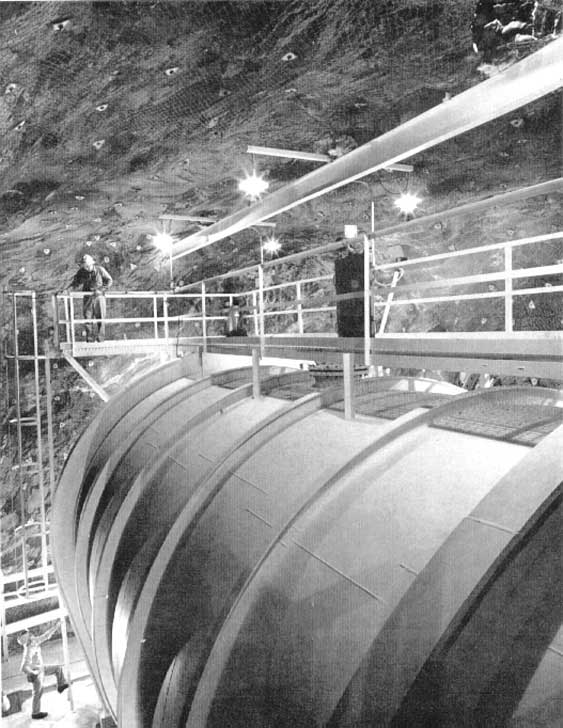

Since the pioneering work of Bethe and others, it was anticipated that the energy of the Sun was produced in its core by the fusion of hydrogen into helium [Wei37,Bet38,Bet39]. This process is accompanied by the emission of neutrinos, which are the only witnesses of the phenomenon. In 1964, John Bahcall developed his first solar model and calculated that the chlorine-argon reaction would be the most promising method to observe solar neutrinos [Bah64]. Simultaneously, Ray Davis revived his chlorine-argon detector [Dav55]. He proposed to install 390 000 liters of perchlorethylene (C2Cl4) in the Homestake Gold mine (South Dakota), deep underground to avoid cosmic rays interaction. Such a detector would observe few 37Cl to 37Ar conversion per day [Dav64]. His first results, in 1968, were a big surprise: Davis observed less than 0.2 37Ar produced per day, much less than the prediction [Dav68]. This is the start of the solar neutrino problem, which will be solved only in 2001. At the end of the 70’s, the solar neutrino deficit was better quantified: (0.39± 0.06) 37Ar were produced per day translated into 2.1±0.3 solar neutrino units and compared to 7.8±1.5 expected from solar models [Cle81]. The final result has been published in 1998 [Cle98].

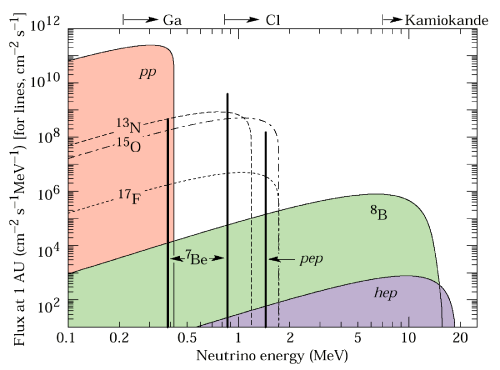

The basic nuclear reaction in the core of the Sun is the fusion of two protons, giving a deuterium, a positron and an electron-neutrino νe. It follows a complicated cycle of nuclear reactions which also produce neutrinos, each with a specific energy spectrum [Fig]. The spectroscopy of solar neutrinos includes: pp-neutrinos, 7Be-neutrinos, pep-neutrinos and 8B neutrinos, with a small amount of CNO-neutrinos. The chlorine experiment of R. Davis was sensitive only to the 7Be- and 8B neutrinos.

After the first chlorine results, many ideas to observe solar neutrinos have been proposed, radiochemical (using gallium, lithium or bromine targets), geochemical (using molybdenum) or direct counting experiments (indium target or elastic interaction on electrons or deuterium). Few of them survived, in spite of beautiful R&D developments.

The first one, a direct counting experiment, was Kamiokande, a large Cerenkov detector (3000 tons of water seen by 1000 PMT’s) designed to observe proton decay. After an improvement of the detector, the solar neutrino detection started in 1986, with a threshold of 7 MeV (i.e. a sensitivity to solar 8B-neutrinos only). Kamiokande observed the scattered electrons from the elastic reaction νe + e⁻ → e⁻ + νe. In 1989, Kamiokande announced to have observed only about 45% of the expected solar neutrinos [Hir89], confirming the solar neutrino problem.

The gallium target was soon considered as very attractive, since it was sensitive to the complete solar neutrino spectrum, including neutrinos from the primary pp fusion reaction. The idea to use the reaction νe +71Ga → e⁻ + 71Ge (followed by the observed 71Ge decay) had been proposed in 1966 [Kuz66], 12 years before the first concrete proposal [Bah78b]. It took again 12 years to see two gallium experiments starting, GALLEX in the Gran Sasso Underground Laboratory (Italy) and SAGE in the Baksan Laboratory (Russia). The first observation of solar pp-neutrinos was announced by GALLEX in June 1992 [Ans92], later confirmed by SAGE [Abd94]. The gallium experiments observed only 60% of the neutrinos predicted by the solar models. The different deficit observed in the different experiments made the solar neutrino problem more and more puzzling.

The solution to the solar neutrino problem (2001-2002)

In the middle of the 90’s, the solar neutrino problem was experimentally established: a deficit of solar νe was observed in the three experiments (chlorine, Kamiokande and gallium). It was reinforced by the measurement provided by the SuperKamiokande experiment in 1998 [Fuk98a], more precise than the Kamiokande one. Three ways to solve the problem were discussed:

- the experiments are wrong (but the check of the gallium experiments with artificial neutrino sources makes this unlikely);

- the solar models are wrong (but the models developed by Bahcall and other independent groups have been considerably improved and now provide relatively similar and stable results);

- the νe produced in the core of the Sun oscillate in νμ or ντ before they reach the Earth.

This exciting third solution became more and more popular, but it had to be proved! At the same period, starting from the observation that the deficit is not uniform, people developed a simple arithmetic mixing the experimental results with the solar model predictions which showed that solar νe coming from the 7Be chain seemed to have completely disappeared. If no serious solar model could accommodate this surprising conclusion, the oscillation mechanism completed by the MSW effect had no difficulty to explain the phenomenon. But the experimental proof was still missing.

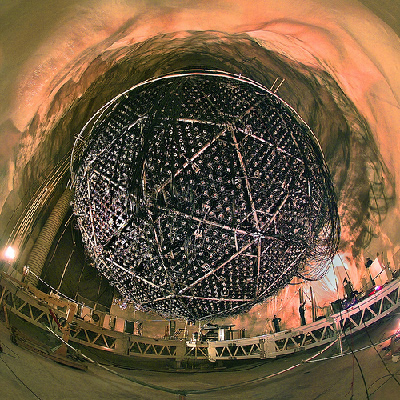

In 1985, Herbert Chen pointed out that the reaction on deuterium νx + d → νx+ p + n (where νx represents any neutrino flavor) would give a direct measurement of the solar neutrino flux, independently of any possible oscillation [Che85]. This was the starting point of the Sudbury Neutrino Observatory (SNO): the use of a large heavy-water Cerenkov detector deep underground in the Sudbury mine (Canada) [Aar87]. It took more than 10 years to build the detector (1000 tons of heavy-water D2O observed by 9500 photomultipliers) which started to take data in November 1999. With a threshold of 6.75 MeV, the detector was sensitive only to 8B solar neutrinos (like SuperKamiokande). The first result, announced in June 2001, was really great: the observed solar νe flux was similar to that observed by SuperKamiokande in normal water (i.e. showing a deficit), but the total flux was similar to the one predicted by solar models (about 5 106 cm-2s-1) [Ahm01]. This was confirmed in April 2002 with a direct measurement of the neutron in the reaction νx + d → νx+ p + n [Ahm02]. The two important results were that solar neutrinos oscillate and that the solar models are correct.

In 1985, Herbert Chen pointed out that the reaction on deuterium νx + d → νx+ p + n (where νx represents any neutrino flavor) would give a direct measurement of the solar neutrino flux, independently of any possible oscillation [Che85]. This was the starting point of the Sudbury Neutrino Observatory (SNO): the use of a large heavy-water Cerenkov detector deep underground in the Sudbury mine (Canada) [Aar87]. It took more than 10 years to build the detector (1000 tons of heavy-water D2O observed by 9500 photomultipliers) which started to take data in November 1999. With a threshold of 6.75 MeV, the detector was sensitive only to 8B solar neutrinos (like SuperKamiokande). The first result, announced in June 2001, was really great: the observed solar νe flux was similar to that observed by SuperKamiokande in normal water (i.e. showing a deficit), but the total flux was similar to the one predicted by solar models (about 5 106 cm-2s-1) [Ahm01]. This was confirmed in April 2002 with a direct measurement of the neutron in the reaction νx + d → νx+ p + n [Ahm02]. The two important results were that solar neutrinos oscillate and that the solar models are correct.

The demonstration that neutrinos oscillate had already been made by the measurement of atmospheric neutrinos in the Superkamiokande experiment in 1998 [Fuk98a], but it concerned oscillation of νμ into ντ. For SNO, the oscillation is between νe and νμ or ντ. The phenomenology of neutrino mixing can be developed and involves three mixing angles θij and two Δm2ij.

The KamLAND experiment, in Japan, by observing antineutrinos from nuclear reactors at a mean distance of about 200 km, confirmed the oscillation observed by the SNO experiment and contributed to the precise determination of the oscillation parameters [Egu03,Ara05b].

In 2014, the Borexino experiment at Gran Sasso observed directly the solar neutrinos produced in the primary proton-proton fusion in the core of the Sun (GALLEX had observed an integral flux) and completed the spectroscopy of solar neutrinos [Bel14]. In 2020, Borexino observed for the first time the solar neutrinos from the so-called CNO cycle [Ago20], which is responsible of only 2% of the energy of the Sun, but which is dominant in more massive stars.

Other tracks for solar neutrino detection |

Beyond the main experiments, many R&D developments using different targets have been performed to study solar neutrinos. We quote:

|

Neutrinos and the Sun |

Almost a century ago, after the first ideas by Eddington in the 20’s, followed by Atkinson and Houtermans [Atk29], physicists assumed that the solar (and stellar) energy was powered by nuclear reactions. The simplest possible reaction, p + p → 2H + e⁺ + n, was first suggested by Carl von Weizsäcker [Wei37] and calculated by Bethe and Critchfield [Bet38]. This fundamental reaction, which  emits the primary pp-neutrinos, was the origin of the so-called pp cycle (different nuclear reactions which are other sources of neutrinos) and Bethe developed also the so-called CNO cycle (which plays a minor role in the Sun but is dominant in more massive stars and produces also neutrinos) [Bet39]. Neutrinos then become privileged witnesses of what happens in the core of the Sun. Our knowledge of the Sun has greatly improved since this time, and neutrinos have played a major role in the deep understanding of “how the Sun shines”. The solar neutrino problem, i.e. the deficit of solar neutrinos observed compared to the predictions of solar models, triggered an intense activity on the experimental side as well as on the theoretical side (solar models and neutrino properties). The great discoveries by SNO were that solar neutrinos are as many as predicted by solar models, and that νe are partially transformed into νμ or ντ proving the neutrino oscillation mechanism. emits the primary pp-neutrinos, was the origin of the so-called pp cycle (different nuclear reactions which are other sources of neutrinos) and Bethe developed also the so-called CNO cycle (which plays a minor role in the Sun but is dominant in more massive stars and produces also neutrinos) [Bet39]. Neutrinos then become privileged witnesses of what happens in the core of the Sun. Our knowledge of the Sun has greatly improved since this time, and neutrinos have played a major role in the deep understanding of “how the Sun shines”. The solar neutrino problem, i.e. the deficit of solar neutrinos observed compared to the predictions of solar models, triggered an intense activity on the experimental side as well as on the theoretical side (solar models and neutrino properties). The great discoveries by SNO were that solar neutrinos are as many as predicted by solar models, and that νe are partially transformed into νμ or ντ proving the neutrino oscillation mechanism. |

In addition to this achievement, the story of solar neutrinos has had further success. Since 2007, the Borexino experiment at the Gran Sasso laboratory has been able to measure with a reasonable precision all the components of the pp cycle (starting with the pp-neutrinos from the initial pp fusion reaction [Bel14], continuing with the pep, 7Be and 8B neutrinos). In 2020 Borexino succeeded in observing for the first time the CNO neutrinos [Ago20] at a value close to the solar model predictions, completing masterfully the spectroscopy of solar neutrinos. The so-called CNO cycle is responsible of about 2% of the energy produced in the Sun, but is dominant in more massive stars.

Brief bibliography on the solar neutrino problem and on solar models

A detailed account of the first steps of the solar neutrino detection and the raise of the “solar neutrino problem” is given by two pioneers in [1]. We also mention the interesting work by Pinch who, motivated by the longstanding solar neutrino problem, studied solar neutrinos from a sociological point of view [2]

[1] John N. Bahcall and Raymond Davis Jr., An account of the development of the solar neutrino problem in “Essays in Nuclear Astrophysics”, Cambridge University Press, 1982, edited by C.A. Barnes, D.D. Clayton, D.N. Schramm;

[2] Trevor Pinch. Confronting Nature, The sociology of Solar-Neutrino Detection, Kluwer/Reidel, 1986

The start of the development of solar models (in the frame of solar neutrino production) is the pioneering paper by John Bahcall [3]. It has been followed by the paper [4] which appeared in 1968 simultaneously with the first result of the chlorine experiment.

[3] J.N. Bahcall. Solar neutrinos. I. Theoretical, Phys. Rev. Lett. 12 (1964) 300

[4] J.N. Bahcall, N.A. Bahcall and G. Shaviv, Present status of the theoretical predictions for the 37Cl solar neutrino experiment, Phys. Rev. Lett. 20 (1968) 1209

Later Bahcall developed the so-called ”standard solar model” (SSM) with different collaborators and published regular updates. The main steps are found in references [5], [6] (solar models takes also into account the helioseismological observations), [7,8] (introduction of the helium and heavy element diffusion in the modeling). Among the other solar models developed over the years, we quote the work by S. Turck-Chièze and collaborators [9]. To explain the solar neutrino problem, many so-called non standard models have been studied; as an example, we quote the reference [10].

[5] J.N. Bahcall, W.F. Huebner, S.H. Lubow, P.D. Parker and R.K. Ulrich, Standard Solar Models and the Uncertainties in Predicted Capture Rates of Solar Neutrinos, Rev. Mod. Phys. 54 (1982) 767

[6] J.N. Bahcall and R.K. Ulrich, Solar Models, Neutrino Experiments and Helioseismology, Rev. Mod. Phys. 60 (1988) 297

[7] John N. Bahcall, M.H. Pinsonneault, Standard solar models, with and without helium diffusion, and the solar neutrino problem, Rev. Mod. Phys. 64 (1992) 885

[8] John N. Bahcall, M. H. Pinsonneault, and G. J. Wasserburg, Solar models with helium and heavy-element diffusion, Rev. Mod. Phys. 67 (1995) 781

[9] S. Turck-Chièze et al., The solar interior, Physics Reports 230 (1993) 57

[10] V. Castellani et al., Solar neutrinos : beyond standard solar models, Physics Reports 281 (1997) 309

After the death of John in 2005, the development of the standard solar model has been pursued by C. Pena-Garay, A. Serenelli and others. The most recent issue is [11].

[11] Núria Vinyoles et al., A new generation of standard solar models, arXiv:1611.09867

A complete account of the first 30 years of the solar neutrinos is given in [12].

[12] John Bahcall, Raymond Davis, Peter Parker, Alexei Smirnov, Roger Ulrich ed., Solar neutrinos: the first thirty years, Addison-Wesley (1994).

In 1989, a first interdisciplinary conference on the Sun was organized in Versailles, covering solar modelling, as well as neutrinos, helioseismology (the other experimental source of information on the interior of the Sun), solar dynamo or transport processes [13]. For science historians, it can also be used as a benchmark: what was known in these years.

[13] G. Berthomieu and M. Cribier, editors, “Inside the Sun”, Proc. of the 121stIAU Colloquium, Versailles, France, May 22-26, 1989, Kluwer Academic Publishers (1990).

Further information

The online Symmetry Magazine published in May 2005 an article on solar neutrinos. and in August 2014 an article on the measurement of Sun’s real-time energy by Borexino.

During the conference on the History of the Neutrino (Sept. 5-7, 2018 in Paris) the history of Solar Neutrinos was reviewed in two talks :

- T. Kirsten (MPI Heidelberg, Germany) for the pioneering experiments : here the slides , the video of his talk and his contribution to the Proceedings.

- A. McDonald (Queen’s University, Canada) for the experiments which brought the solution to the solar neutrino problem : here the slides , the video of his talk and his contribution to the Proceedings.

References

| Author(s) | Title | Reference | Key-words | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aar87 | G. Aardsma et al. | A heavy water detector to resolve the solar neutrino problem | Phys. Lett. B 194 (1987) 321 | solar detection solarbib detectorbib |

| Abd02 | J.N. Abdurashitov et al., SAGE collaboration | Solar neutrino flux measurements by the Soviet-American Gallium Experiment (SAGE) for half the 22 year solar cycle | J.Exp.Theor.Phys. 95 (2002) 181-193; arXiv:astro-ph/0204245 | solar solarbib |

| Abd09 | J.N. Abdurashitov et al. | Measurement of the solar neutrino capture rate with gallium metal. III: Results for the 2002--2007 data-taking period | Phys. Rev. C80 (2009) 015807; arXiv:0901.2200 | solar detection solarbib |

| Abd94 | J.N. Abdurashitov et al. | Results from SAGE (The Russian-American Gallium solar neutrino experiment) | Phys. Lett. B328 (1994) 234 | solar solarbib plotbib |

| Ade98 | E. Adelberger et al. | Solar fusion cross sections | Rev. Mod. Phys. 70 (1998) 1265 | solar solarbib |

| Ago20 | M. Agostini et al., Borexino Collaboration | Experimental evidence of neutrinos produced in the CNO fusion cycle in the Sun | Nature 587 (2020) 577; arXiv:2006.15115 | historical solar milestonebib overviewbib solarbib |

| Ahm01 | Q.R. Ahmad et al., SNO collaboration | Measurement of the rate ne + d → p + p + e- interactions produced by 8B solar neutrinos at the Sudbury Neutrino Observatory | Phys. Rev. Lett. 87 (2001) 071301; arXiv:nucl-ex/0106015 | historical solar oscillation msw milestonebib overviewbib solarbib oscbib plotbib |

| Ahm02 | Q.R. Ahmad et al., SNO collaboration | Direct evidence for neutrino flavor transformation from neutral-current interactions in the Sudbury Neutrino Observatory | Phys. Rev. Lett. 89 (2002) 011301; arXiv:nucl-ex/0204008 | historical solar oscillation msw milestonebib overviewbib solarbib oscbib plotbib |

| Ans92 | P. Anselmann et al., Gallex collaboration | Solar neutrinos observed by GALLEX at Gran Sasso | Phys. Lett. B285 (1992) 376 | historical solar milestonebib overviewbib solarbib plotbib |

| Atk29 | R. d'E. Atkinson and F.G. Houtermans | Zur Frage der Aufbaumöglichtkeit der Elementen in Sternen | Z. Phys. 54 (1929) 656 | historical solar solarbib |

| Bah64 | J.N. Bahcall | Solar neutrinos. I. Theoretical | Phys. Rev. Lett. 12 (1964) 300 | historical solar overviewbib solarbib |

| Bah78b | John N. Bahcall et al. | Proposed solar neutrino experiment using Ga-71 | Phys. Rev. Lett. 40 (1978) 1351 | solar detection solarbib |

| Bah86 | J.N. Bahcall, M. Baldo-Ceolin, D.B. Cline, C. Rubbia | Prediction for a liquid argon solar neutrino detector | Phys. Lett. B178 (1986) 324 | solar detection solarbib |

| Bel14 | G. Bellini et al., Borexino collaboration | Neutrinos from the primary proton-proton fusion in the Sun | Nature 512 (2014) 383 | historical solar milestonebib overviewbib solarbib |

| Bet38 | H.A. Bethe and C.L. Critchfield | The formation of deuterons by proton combination | Phys. Rev. 54 (1938) 248 | historical solar overviewbib solarbib |

| Bet39 | H.A. Bethe | Energy production in stars | Phys. Rev. 55 (1939) 434 | historical solar milestonebib overviewbib solarbib |

| Che85 | H.H. Chen | Direct Approach to Resolve the Solar-Neutrino Problem | Phys. Rev. Lett. 55 (1985) 1534 | solar detection solarbib |

| Cle81 | B.T. Cleveland, R. Davis and J.K. Rowley | Solar neutrino experiments and neutrino oscillations | AIP Conference Proc. 72 (1981) 322 | solar oscillation solarbib |

| Cle98 | B.T. Cleveland et al. | Measurement of the solar electron neutrino flux with the Homestake chlorine detector | Astrophysical Journal 496 (1998) 505 | solar solarbib plotbib |

| Cow82 | G.A. Cowan and W.C. Haxton | Solar neutrino production of technetium-97 and technetium-98 | Science 216 (1982) 51 | solar detection solarbib |

| Dav55 | Raymond Davis Jr. | Attempt to Detect the Antineutrino from a Nuclear Reactor by the 37Cl(neutrino,e-)37Ar reaction | Phys. Rev. 97 (1955) 766 | historical properties detection numbernu discovbib solarbib nuantinubib |

| Dav64 | R. Davis, Jr. | Solar neutrinos. II. Experimental | Phys. Rev. Lett. 12 (1964) 303 | historical solar overviewbib solarbib nuantinubib |

| Fuk96 | Y. Fukuda et al. | Solar neutrino data covering solar cycle 22 | Phys. Rev. Lett. 77 (1996) 1683 | solar overviewbib solarbib |

| Fuk98a | Y. Fukuda et al., Super-Kamiokande collaboration | Measurements of the solar neutrino flux from Super-Kamiokande’s first 300 days | Phys. Rev. Lett. 81 (1998) 1158 | solar solarbib |

| Gor01 | Ph. Gorodetzky, HELLAZ collaboration | The solar neutrino project HELLAZ: status report on the hardware and on the simulation | Nucl. Instr. and Methods A471 (2001) 131 | solar detection solarbib |

| Ham98 | W. Hampel et al., Gallex collaboration | Final results of the 51Cr neutrino source experiment in GALLEX | Phys. Lett. B420 (1998) 114 | solar solarbib |

| Ham99 | W. Hampel et al., Gallex collaboration | GALLEX solar neutrino observations: results for GALLEX-IV | Phys. Lett. B447 (1999) 127 | solar solarbib |

| Hax88 | W.C. Haxton | Radiochemical neutrino detection via 127I(ne,e-)127Xe | Phys. Rev. Lett. 60 (1988) 768 | solar detection solarbib |

| Hir89 | K.S. Hirata et al. | Observation of 8B solar neutrinos in the Kamiokande-II detector | Phys. Rev. Lett. 63 (1989) 16 | solar milestonebib overviewbib solarbib |

| Hua07 | Y.H.Huang et al. | Potential for precision measurement of solar neutrino luminosity by HERON | arXiv:0711.4095 | solar detection solarbib |

| Hur84 | G.S. Hurst et al. | Feasibility of a 81Br(neutrino,e-)81Kr solar neutrino experiment | Phys. Rev. Lett. 53 (1984) 1116 | solar detection solarbib |

| Kae10 | F. Kaether, W. Hampel, G. Heusser, J. Kiko, T. Kirsten | Reanalysis of the GALLEX solar neutrino flux and source experiments | Phys. Lett. B685 (2010) 47; arXiv:1001.2731 | solar solarbib |

| Kop09 | A.V. Kopylov et al. | A lithium-beryllium method for the detection of solar neutrinos | arXiv:0910.3889 | solar detection solarbib |

| Kuz66 | V.A. Kuzmin | Detection of solar neutrinos by means of 71Ga(neutrino,e-)71Ge reaction | Sov. Phys. JETP 22 (1966) 1051 | solar detection solarbib |

| Lan87 | R.E. Lanou, H.J. Maris, G.M. Seidl | Detection of solar neutrinos in superfluid helium | Phys. Rev. Lett. 58 (1987) 2498 | solar detection solarbib |

| Rag01 | R.S. Raghavan | pp-solar neutrino spectroscopy; return tof the indium detector | arXiv:hep-ex/0106054 | solar detection solarbib |

| Rag97 | R.S. Raghavan | New prospects for real-time spectroscopy of low energy electron neutrinos from the Sun | Phys. Rev. Lett. 78 (1997) 3618 | solar detection solarbib |

| Seg92 | J. Séguinot, T. Ypsilantis, A. Zichichi | A high rate solar neutrino detector with energy determination | Report Collège de France LPC 92-31 (1992) | solar detection solarbib |

| Vin16 | N. Vinyoles et al. | A new generation of standard solar models | arXiv:1611.09867 | solar solarbib |

| Wei37 | C.F. von Weizsäcker | Über Elementumwandlungen im Innern der Sterne | Physikalisches Zeitschrift 38 (1937) 176 - "On the transformation of elements in the core of stars" | historical solar solarbib |

In august 1984 a solar neutrino conference was held in Lead (South Dakota) the city close to the Homestake gold mine where the Davis’s experiment was running. Participants stayed in Deadwood, an historic city where Bill Hickok, Calamity Jane and Seth Bullock are burried, a city as in western movies.

During the reception celebrating the 70th Davis’s birthday many stories were told. I remember one : « To go to the experiment, Davis has to use the elevator as the miners. An elevator full of mud, watered permanently to avoid fire, and descending at high speed in a terrible noise. After the first results of the chlorine experiment, Davis looks concerned. Then an old miners told him : Don’t worry Professor, the summer was really bad this year »